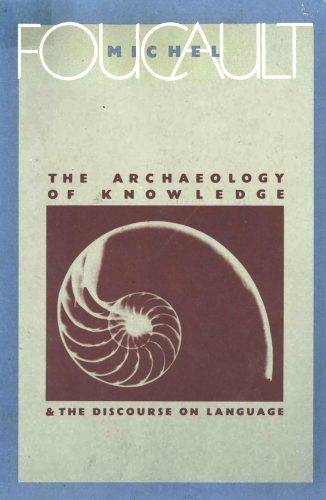

The Archaeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language by Michel Foucault

The Archaeology of Knowledge

and The Discourse on Language

Madness, sexuality, power, knowledge — are these facts of life or simply parts of speech? In a series of works of astonishing brilliance, historian Michel Foucault has excavated the hidden assumptions that govern the way we live and the way we think. The Archaeology of Knowledge begins at the of “things said” and moves quickly to illuminate the connections between knowledge, language, and action in a style at once profound and personal. A summing up of Foucault’s own methodological assumptions, this book is also a first step toward a genealogy of the way we live now. Challenging, at times infuriating, it is an absolutely indispensable guide to one of the most innovative thinkers now writing.

Book Details

Author: Michel Foucault

Print Length: 240

Publisher: Pantheon Books

Submitted by: Robert

Book format: Pdf

Language: English

Book Download

Contents

PART I. INTRODUCTION

- Introduction

PART II. THE DISCURSIVE REGULARITIES

- The unities of discourse

- Discursive formations

- The formation of objects

- The formation of enunciative modalities

- The formation of concepts

- The formation of strategies

- Remarks and consequences

PART III. THE STATEMENT AND THE ARCHIVE

- Defining the statement

- The enunciative function

- The description of statements

- Rarity, exteriority, accumulation

- The historical a priori and the archive

PART IV. ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION

- Archaeology and the history of ideas

- The original and the regular

- Contradictions

- The comparative facts

- Change and transformations

- Science and knowledge

PART V. CONCLUSION

- Conclusion

- Appendix: The Discourse on Language Index

Sample

The Archaeology of Knowledge

and The Discourse on Language

Introduction

For many years now historians have preferred to turn their attention to long periods, as if, beneath the shifts and changes of political events, they were trying to reveal the stable, almost indestructible system of checks and balances, the irreversible processes, the constant readjustments, the underlying tendencies that gather force, and are then suddenly reversed after centuries of continuity, the movements of accumulation and slow saturation, the great silent, motionless bases that traditional history has covered with a thick layer of events. The tools that enable historians to carry out this work of analysis are partly inherited and partly of their own making: models of economic growth, quantitative analysis of market movements, accounts of demographic expansion and contraction, the study of climate and its long-term changes, the fixing of sociological constants, the description of technological adjustments and of their spread and continuity. These tools have enabled workers in the historical field to distinguish various sedimentary strata; linear successions, which for so long had been the object of research, have given way to discoveries in depth. From the political mobility at the surface down to the slow movements of’material civilization’, ever more levels of analysis have been established: each has its own peculiar discontinuities and patterns; and as one descends to the deepest levels, the rhythms become broader. Beneath the rapidly changing history of governments, wars, and famines, there emerge other, apparently unmoving histories: the history of sea routes, the history of com or of gold-mining, the history of drought and of irrigation, the history of crop rotation, the history of the balance achieved by the human species between hunger and abundance. The old questions of the traditional analysis (What link should be made between disparate events? How can a causal succession be established between them? What continuity or overall significance do they possess? Is it possible to define a totality, or must one be content with reconstituting connexions?) are now being replaced by questions of another type: which strata should be isolated from others? What types of series should be established? What criteria of periodization should be adopted for each of them? What system of relations (hierarchy, dominance, stratification, univocal determination, circular causality) may be established between them? What series of series may be established? And in what large-scale chronological table may distinct series of events be determined?

…

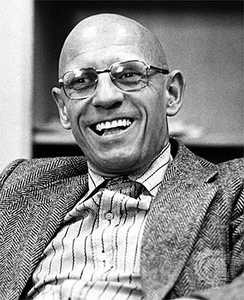

Foucault’s theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a post-structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels, preferring to present his thought as a critical history of modernity. His thought has influenced academics, especially those working in communication studies, sociology, cultural studies, literary theory, feminism, and critical theory. Activist groups have also found his theories compelling.About Author: Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984), generally known as Michel Foucault (French: [miʃɛl fuko]), was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic.

Paul-Michel Foucault (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984), generally known as Michel Foucault (French: [miʃɛl fuko]), was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!