Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason by Michel Foucault

Madness and Civilization

A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason

Michel Foucault examines the archeology of madness in the West from 1500 to 1800 – from the late Middle Ages, when insanity was still considered part of everyday life and fools and lunatics walked the streets freely, to the time when such people began to be considered a threat, asylums were first built, and walls were erected between the “insane” and the rest of humanity.

Foucault traces the evolution of the concept of madness through three phases: the Renaissance, the “Classical Age” (the later seventeenth and most of the eighteenth centuries) and the modern experience. He argues that in the Renaissance the mad were portrayed in art as possessing a kind of wisdom – a knowledge of the limits of our world – and portrayed in literature as revealing the distinction between what men are and what they pretend to be. Renaissance art and literature depicted the mad as engaged with the reasonable while representing the mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy but the Renaissance also marked the beginning of an objective description of reason and unreason (as though seen from above) compared with the more intimate medieval descriptions from within society.

Book Details

Author: Michel Foucault

Print Length: 311

Publisher: Random House

Submitted by: Robert

Book format: Pdf

Language: English

Book Download

Contents

- “Stultifera Navis”

- The Great Confinement

- The Insane

- Passion and Delirium

- Aspects of Madness

- Doctors and Patients

- The Great Fear

- The New Division

- The Birth of the Asylum

- Conclusion

- Notes

Sample

Madness and Civilization

A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason

Introduction

Michel Foucault has achieved something truly creative in this book on the history of madness during the so-called classical age: the end of the sixteenth and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Rather than to review historically the concept of madness, the author has chosen to recreate, mostly from original documents, mental illness, folly, and unreason as they must have existed in their time, place, and proper social perspective. In a sense, he has tried to re-create the negative part of the concept, that which has disappeared under the retroactive influence of present-day ideas and the passage of time. Too many historical books about psychic disorders look at the past in the light of the present; they single out only what has positive and direct relevance to present-day psychiatry. This book belongs to the few which demonstrate how skillful, sensitive scholarship uses history to enrich, deepen, and reveal new avenues for thought and investigation.

No oversimplifications, no black-and-white statements, no sweeping generalizations are ever allowed in this book; folly is brought back to life as a complex social phenomenon, part and parcel of the human condition. Most of the time, for the sake of clarity, we examine madness through one of its facets; as M. Foucault animates one facet of the problem after the other, he always keeps them related to each other. The end of the Middle Ages emphasized the comic, but just as often the tragic aspect of madness, as in Tristan and Iseult, for example. The Renaissance, with Erasmus’s Praise of Folly, demonstrated how fascinating imagination and some of its vagaries were to the thinkers of that day. The French Revolution, Pinel, and Tuke emphasized political, legal, medical, or religious aspects of madness; and today, our so-called objective medical approach, in spite of the benefit that it has brought to the mentally ill, continues to look at only one side of the picture. Folly is so human that it has common roots with poetry and tragedy; it is revealed as much in the insane asylum as in the writings of a Cervantes or a Shakespeare, or in the deep psychological insights and cries of revolt of a Nietzsche. Correctly or incorrectly, the author feels that Freud’s death instinct also seems from the tragic elements which led men of all epochs to worship, laugh at, and dread folly simultaneously; Fascinating as Renaissance men found it— they painted it, praised it, sang about it一it also heralded for them death of the body by picturing death of the mind.

Nothing is more illuminating than to follow with M. Foucault the many threads which are woven in this complex book, whether it speaks of changing symptoms, commitment procedures, or treatment. For example: he sees a definite connection between some of the attitudes toward madness and the disappearance, between 1200 and 1400, of leprosy. In the middle of the twelfth century, France had more than 2,000 leprosarioms, and England and Scotland 220 for a population of a million and a half people. As leprosy vanished, in part because of segregation, a void was created and the moral values attached to the leper had to find another scapegoat. Mental illness and unreason attracted that stigma to themselves, but even this was neither complete, sunple^ nor immediate.

…

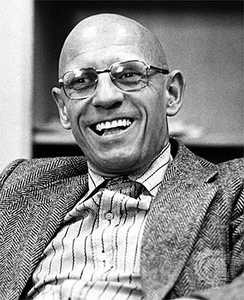

Foucault’s theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a post-structuralist and postmodernist, Foucault rejected these labels, preferring to present his thought as a critical history of modernity. His thought has influenced academics, especially those working in communication studies, sociology, cultural studies, literary theory, feminism, and critical theory. Activist groups have also found his theories compelling.About Author: Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984), generally known as Michel Foucault (French: [miʃɛl fuko]), was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic.

Paul-Michel Foucault (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984), generally known as Michel Foucault (French: [miʃɛl fuko]), was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, and literary critic.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!